"While the common opioid epidemic narrative is one of it all starting with prescribed use, a story of people being duped by big pharma and irresponsible doctors, that was not my opioid experience, nor the experience of most people I know."

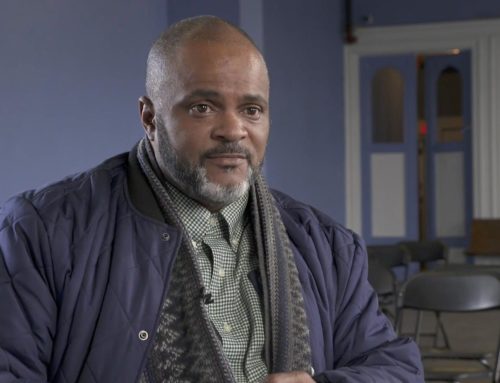

Today I am 37 years old, a person in recovery, a partner, a parent, an Ivy League school graduate, a social worker, a member of the LGBTQ+ community, and so much more.

With the dominant narrative of the opioid epidemic, you may be expecting my opioid story to go something like this: “I never used drugs, never would use drugs, was prescribed opioids for pain, got duped into believing they were safe, took them exactly as prescribed, and wound up addicted.”

Well, that is not my story – and in fact, it is not the story of most who develop an opioid use disorder.

A big part of my story is that I grew up in Northeast Philadelphia during the War on Drugs era. All around me – in the media and in the D.A.R.E. programming at school – I was surrounded by the rhetoric that drugs are bad, people who use drugs are bad, and if you want to not be a bad person doing bad things, then just say no to drugs. My biological mother was not a part of my life growing up due to her own struggles with addiction, and the message I received at home was: if your mom really wanted to be a mom, she would stop choosing to use drugs. I grew up being taught from the world around me and in turn believing that addiction was a choice. And, I couldn’t for the life of me understand why my mom would choose drugs over being the mom I missed, craved, and needed.

Around 12 years old, I started using various substances. First it was alcohol, then marijuana, and then various pills like Xanax or whatever I could get my hands on. Around this same time, I learned that my mom died of a heroin overdose. Learning of my mom’s death was a traumatic experience for me and resulted in a breaking point. I was already tremendously unhappy and, after I learned of my mom’s death, I struggled even more with depression and thoughts of suicide. My drug use coincided with these mental health challenges and the trauma of losing my mom – not just once when she abandoned me, but twice when I learned she died. As soon as I discovered that alcohol and other drugs could numb my pain and allow me to escape for a bit, I wanted as much of that feeling as I could get, as often as possible. By the time I was 13, my mental health and substance use challenges landed me in my first institution, and the next four years became a repeat cycle of institutionalization. I would go into an institution, be heavily medicated, come home, return right back to using and reckless behavior, then wind up back in another institution. I spent my entire teenage years trapped in this cycle.

I hated being in institutions, and when I was 15 years old, I decided to steal a car from a residential treatment facility in an attempt to run away. This great escape lasted all of about 10 minutes and led to me right to the juvenile justice system. To be frank, my experience with Philly’s juvenile justice system only added more trauma that I would go on to spend years healing from. While I sat in the detention center, my sole focus became “getting out of the system.” After having spent so much time in institutions, I had learned what the authority figures wanted to hear, and I had also learned that by just shutting up and being compliant, I would get out sooner. My goal at that time wasn’t to get better: it was simply to get out. And get out I did. I was released from my last youth placement after five months without ever addressing the challenges that had brought me there. It turned out that in the process of convincing the psychiatrists, counselors, probation officer, judge, my parents, and everyone else that I was all better, I had also tricked myself into believing that I was better.

I managed to go back to high school, play basketball and softball, graduate and receive a basketball scholarship to Manor College. Right before graduating high school, I came off probation and decided to celebrate this milestone by smoking marijuana. It was going to be just one time and that was it. That one time, however, quickly took me right back to problematic use, which led back to other substances. By my first semester in college, I was right back to where I had been before. My basketball coach told me that I needed to either get it together or I was off the team. I wasn’t offered any resources or support, wasn’t directed to the counseling office, and wasn’t given any tools for how exactly I was supposed to get it together. I felt so overwhelmed by the idea of being able to “get it together” that I just dropped out and walked away from a full basketball scholarship. This was really where things spiraled downward. By the time I was 21, I was dating someone who was using prescription opioids that she was buying off the street for the purpose of getting high. I tried them and quickly came to love the feeling they gave me. I had spent much of my life wanting to feel good, and here was this drug that gave me what I had been craving for so long. While the common opioid epidemic narrative is one of it all starting with prescribed use, a story of people being duped by big pharma and irresponsible doctors, that was not my opioid experience, nor the experience of most people I know. I used diverted prescription opioids for the purpose of getting high. I knew what I was doing, I knew that the way I was using them could be addictive; I just thought, like so many others, that addiction would never happen to me. I thought that I would be able to stop when I wanted to. That was, after all, what I had been taught growing up – that addiction is a choice.

If I had to pick labels I would identify as a lesbian, gender non-conforming woman. For me, substance use was a way to escape discomfort; and there’s nothing that I’ve experienced that is quite as uncomfortable as walking through the world as your authentic self yet getting the message everywhere you turn that this world is not designed for you and that you are a minority. I got that message early on in life, so it doesn’t surprise me that people who identify as members of LGBTQ+ communities are at a higher risk for mental health and substance use concerns. Even today, I get some anxiety when I enter a public bathroom because I’ve had people give me looks or ask me if I know this is the ladies room. I will say, “I know. I belong here,” but that’s an uncomfortable experience. There’s still a lot of discrimination and a lot of hatred, yet the desire to feel accepted and connected is a human desire. Learning to live life in a world that remains often unaffirming of who I am, without escaping and numbing through drugs, has been a work in progress, and therapy has been the most instrumental support for me.

For a long time, I wasn’t willing to admit that I was addicted and that I had become just like my mom, a woman I had so much anger toward back then. It wasn’t until persistent opioid use with persistent thoughts of suicide consumed my entire life that I came face-to-face with accepting that I had a serious problem. I realized I needed to seek help to address my mental health challenges and eventually became committed to working on my substance use challenges as well. I started outpatient treatment but was unable to stop using. At this point, thoughts of suicide were a daily occurrence, and I desperately wanted to stop using, so I had to make the decision to enter into the very same type of place I had spent my entire adolescent life trying to get out of: inpatient treatment.

I went to the crisis response center first, and then went to a 28-day rehab program and was offered a six-month long-term treatment program. Although I left the program after three months and returned back to using, I couldn’t escape this feeling that I knew what I was doing was not the best thing for me. It didn’t take long for me to go back to seeking help. I had an interview with a recovery house called Fresh Start in Kensington, but the director told me they didn’t have any beds available for walk-ins. I remember feeling defeated and at the end of my rope, but then she said, “I see something in you. Let me see if I can call in a favor.” The difference between life and death for me was somebody’s willingness to call in a favor and that she saw potential in me. That moment fuels a lot of my advocacy because that favor saved my life 14 years ago. My life shouldn’t have hinged on a called in favor, and access to recovery should never be about luck, privilege, favors, presenting well, or knowing the right people. Recovery should be available to everybody with equity.

I’ve always felt a call to serve others, but it really wasn’t until I did the work to help myself first that I was even able to have that possibility. I was asked to come back to work at the recovery house that started my journey to recovery. Then, I worked for the Philadelphia Recovery Community Center for almost three years. That experience introduced me to the world of advocacy, and I fell in love instantly. In advocacy, I think it’s important to share our stories in ways that make sure solutions aren’t only centered on one demographic but rather benefit all people who use all drugs.

Addiction, in my experience personally and professionally, is less about the substance being used and more about what’s driving that substance use. It’s important that I share my truth to counter what I see as false narratives that can lead to policies, practices, and funding not aimed at solutions to the real problems. For example, at one point in my active addiction, I didn’t have money to get high and somebody told me that you could suck on a Freon tank used for air conditioning to get a high. Well, I spent a few days in a row sucking on a big ‘ole green Freon tank, walking down the street with it in my arms in Northeast Philly. The solution to addressing my substance use disorder wouldn’t be to eradicate the world of Freon tanks. The solution comes from understanding what was driving me to want to escape so badly that I would literally wrap my mouth around a Freon tank and suck on it. If we really want to reach a solution, we first need to be honest and authentic about what drives our use. We can’t simply focus on supply; we need to understand and address the demand. And, we can’t simply focus on opioids; we need to understand and address what drives all substance use, from alcohol to opioids to crack cocaine.

This is why I am sharing my story. There is so much stigma surrounding mental illness, trauma, and substance use, and that stigma creates huge barriers for people to feel safe to open up and seek help. There is also so much misinformation and a faulty narrative surrounding the opioid epidemic, and this is leading to tremendous harm – both for people who benefit from prescription opioids for pain and for people who live with a substance use disorder. I share the truth of my opioid story because I now know that people who use drugs aren’t bad people, regardless of the drug used or how they came to use them. The person who started using opioids for the purpose of getting high is not a bad person; the person smoking crack cocaine is not a bad person; the people we have locked up for their drug use through the War on Drugs are not bad people. I now know that people who struggle with addiction most certainly did not choose to become addicted – that like me, and probably like my mom, most people believe that addiction will never happen to them. I share my opioid story because we need to move beyond just looking at opioids. We need to move beyond the opioid epidemic’s whitewashed tale of addiction. And, I share my opioid story to give hope that regardless of what drugs we used, how we came to use them, what we look like, how much money we have, or what we’ve experienced in life, we can and do recover when given the resources, support, and services we need, when we need and for how long we need them.